Empire of Japan (1935-1943)

Empire of Japan (1935-1943)

Armored Railroad Car / Tankette – 121-138 Built

Occupational Hazard

The Type 95 So-Ki was an armored railroad car and tankette. It had the niche ability to drive on both the ground with its tracks, and on railroads with its retractable railroad wheels. It was technically classified as an engineering vehicle by the Japanese, and was developed likely in response to significant Chinese guerrilla resistance campaigns around the railways in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, where the vehicles appear to have seen most of their service. A small (but unknown) number were also fielded in Burma, and a handful were captured and reused by the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese Nationalists) in Manchuria at some point between 1937 and 1945. These KMT So-Ki tankettes were later captured by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army during the Chinese Civil War (1946-1950) and reused by their new owners.

Type 95 So-Ki of the People’s Liberation Army, on display in the PLA Tank museum in Beijing. Note the damage on the right of the large hull hatch.

Context: Occupation of Manchuria

The Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation of Manchuria began on September 18th, 1931, following the Mukden Incident. The Mukden Incident was a staged operation by the Kwantung Army in order to justify further expansion into China. In short, a Japanese officer planted a small amount of dynamite near the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railway in Mukden, which caused very light damage to a bridge. The Japanese blamed the incident on local Chinese dissidents and as a result, the Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria and established the puppet-state of Manchukuo.

Significant movements to resist the occupation were undertaken by Chinese guerrilla fighters, despite orders from the Chinese President, Chiang Kai-shek, not to do so. One of the biggest examples of this resistance was on 4th November, 1931, when the acting governor of Heilongjiang, General Ma Zhanshan, set up a defense on Nenjiang bridge (which was a railway bridge over the Nen River) in order to prevent the Japanese crossing into Heilongjiang Province. The bridge had been dynamited earlier during fighting against the puppet Manchukuo Imperial Army forces of General Zhang Haipeng, but the Japanese sent a repair team escorted by 800 soldiers to fix the bridge.

Ma fielded an estimated 2500 soldiers who opened fire on the Japanese forces late in the day on 4th November in a skirmish that lasted more than three hours. By the end, 120 soldiers of Ma’s forces were dead, but only 15 Japanese were killed in the fighting. Ma’s forces were eventually chased off but later counterattacked. However, they were unable to recapture the bridge due to significant Japanese artillery fire and the presence of Japanese tanks. Between November 5th and 15th, the Japanese managed to kill 400 of Ma’s forces, and wound 300 more.

By this point, Ma’s forces were holed up in the nearby city of Qiqihar, and were ordered to surrender by the Japanese. This order was refused, and on 17th November, the city was besieged by 3500 Japanese soldiers of the 2nd Division. The city was defended by an estimated 8000 Chinese soldiers, but the defenders were inferior in training, leadership, and equipment to the Japanese. Japanese cavalry made the initial breakthrough, and artillery and airpower prevented any Chinese counterattacks which could otherwise have prevented the breakthrough. On November 18th, Ma began evacuating the city, and the next day, his remnant forces fled to other cities to put up their final resistance.

Many other resistance fighters later retreated into nearby Rehe Province (which was still part of Nationalist China at that time), but tens of thousands of others split into smaller guerrilla forces in order to continue resistance. An estimated 120,000 guerrilla fighters were operating in 1933, declining to 50,000 in 1934, and then declining by 10,000 every year until 1938. The CCP (Chinese Communist Party) began to appeal to many of these guerrillas, who willingly signed up with the CCP in order to continue resistance.

Against this background, it seems as though the Japanese wanted an anti-partisan vehicle that was capable of safely transporting soldiers in order to defend railways from these guerrilla fighters. The Kwantung Army had been in favor of light patrol vehicles which could patrol railways independently of large locomotives. The Type 93 So-Mo armored car was one such development, which had wheels for tracks, and wheels for the road. Around 1000 of these were made, and were perfect for transporting railway repair teams. However, it seems as though the Kwantung Army also wanted a tankette in order to provide greater protection for its crews, and the fear factor of a tank. This appears to have been the genesis of the Type 95 So-Ki.

Design Process

The Type 95 So-Ki was produced by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Tokyo Gas Electric Industry. Production lasted from 1935 – 1943, but total production figures are somewhat unclear. Akira Takizawa reports 121 built, but Steven Zaloga reports 138 in “New Vanguard 140 – Armored Trains“. Leland Ness also reports that in 1941, 29 were built, 16 in 1942, and only 9 in 1943, but does not provide total figures.

In any case, the vehicle was a very sophisticated design, loosely based on the Ha-Go chassis, but featured tank tracks for the ground, and retractable wheels for railways. These retractable wheels were hidden either side of the tracks below the hull, and as such, they are usually out of sight in photos.

Takizawa reports that it took only a minute to turn from railway to track mode, and only three minutes to turn from track to railway mode, and this could be done from within the tankette, making the operation safe for the crew. Takizawa also reports that the vehicle’s wheels could be changed to fit narrow (1067mm), standard (1435mm), and broad (1524mm) gauge tracks, although Zaloga only makes reference to the tankette being able to fit on narrow gauge tracks.

Technical drawing of the Type 95 So-Ki.

The vehicle had only 6 mm of armor, except for the turret, which had 8 mm. This was just enough to defend against small arms fire, which was acceptable because Chinese guerrillas did not typically field anything larger than the usual small arms consisting of rifles and grenades. The tankette could carry a commander/driver and five soldiers. The passengers were typically armed with rifles, and sometimes a Type 11 machine gun, which would be shot from the various firing ports around the vehicle. The vehicle had no standard mounted armament because it was officially classified as an engineering vehicle, and if it were to receive an standard armament, the vehicles would no longer belong to the IJA’s engineers, but to their tankers.

Top speed on rails was up to 45 mph (72 km/h), and if towing a trailer, this was reduced to a mere 25 mph (40 km/h). On its tracks, it could reach up to 19 mph (30 km/h). Photos also show that several So-Ki tanks could link up in order to tow heavier loads on rails.

Crane-carrying vehicles were also developed on the chassis of the So-Ki for larger engineering operations, this almost certainly being the Type 2 Ri-Ki, but further information on this rare vehicle is lacking.

Combat

The vehicle was deployed primarily in Manchuria from 1938, with an estimated 98 being fielded there. They were deployed in every railroad regiment typically as a guard vehicle, or as a transport for munitions and equipment. In non-combat roles, photos show that several So-Ki tankettes would link up to tow heavier loads.

Type 95 So-Ki on rails. Undated, unlocated, likely Manchuria pre-1937.

So-Ki tankettes are also reported to have seen service during offensive invasion operations (presumably railway-borne operations only), but this seems to have been a very rare occurrence. Even when used defensively, these vehicles were particularly troublesome for the Chinese troops (of various armies and warlords) that they encountered, because none of them had any effective anti-tank weapons.

A small but unknown number were also used during the Burma campaigns, although further details are unclear. These, too, were likely used for patrol duties.

One vehicle currently stands in Kubinka tank museum, apparently captured by the Red Army in Manchuria in August, 1945 during the Manchurian Strategic Operation Offensive. Another vehicle was captured by the US in Burma, and was shipped back to the US for further study.

Chinese Service

At the end of WWII, an estimated 1.5-1.6 million Japanese were left in China, with 1.1 million being in Manchuria (formerly Manchukuo), and just over 500,000 in other areas (overwhelmingly these were in Formosa, nowadays Taiwan, with 479,000, but Hong Kong and other areas also hosted thousands). In the years 1945-1948, a mass repatriation effort was initiated by the United States under Kuomintang auspices to repatriate those nationals back to Japan. However, in 1945, the ageing warlord of Shanxi Province, Yan Xishan (閻錫山), secretly recruited thousands of former Japanese soldiers into his private army who took their equipment with them. This was kept secret from both Communist and American forces. Estimates suggest that up to 10,000 Japanese soldiers were among his ranks, including a small number of Type 95 So-Ki tankettes.

Like many warlords during the civil war, Xishan was ostensibly allied to the KMT, but only in that it served his personal interests to have a stable and relatively conservative government in control of China which was let him maintain de facto control of the province. As such, Xishan and his private army were instrumental to keeping Shanxi Province from falling into Communist hands.

It is reported that the tankettes of the Xishan Army were used patrol the Tongpu (nowadays Datong–Puzhou) and Jingjing railway lines, and saw major combat duties during the PLA’s Taiyuan Campaign (5th October 1948 – 24th April 1949). This campaign was swift and brutal, leaving only a few cities either side of each railway line under Xishan’s control by late 1948. At the end of the Taiyuan Campaign, these tankettes were abandoned and at least one was captured and reused by the PLA. This So-Ki is now on display in the tank museum in Beijing with PLA markings.

Several Type 95 So-Ki tankettes were photographed by Mark Kauffman for TIME Magazine in February 1947, in Laiwu, Shandong Province. However, it is unclear with whom these tankettes were serving. The soldiers in the photo appear to be Nationalist soldiers, but could be soldiers of the Xishan Army. That said, it is not known that the Xishan Army operated in Shandong Province. Therefore, these could be other Type 95 So-Ki tankettes in service with another army, most likely the NRA.

Type 95 So-Ki specifications |

|

| Dimensions (L-w-h) | 4.9m x 2.6m x 2.54m (on railroad), 2.43m (on tracks) (16.1 ft x 8.53 ft x 8.3 ft OR 7.97 ft) |

| Total weight, battle ready | 8700kg (9.59 US tons) |

| Crew | 6 – 1+5, (Commander/driver and 5 passengers) |

| Propulsion | Unknown gasoline engine, 84hp @2400 RPM |

| Top speed | On tracks – 30 km/h (19 mph). On rails – 72 km/h (45 mph). On rails, towing a trailer – 40 km/h (25 mph) |

| Armor | 6-8 mm (0.24 – 0.31 in) |

| Armament | None – passengers carried rifles and sometimes a Type 11 machine gun. |

| Range | Unknown. |

| Total production | 121 – 138 |

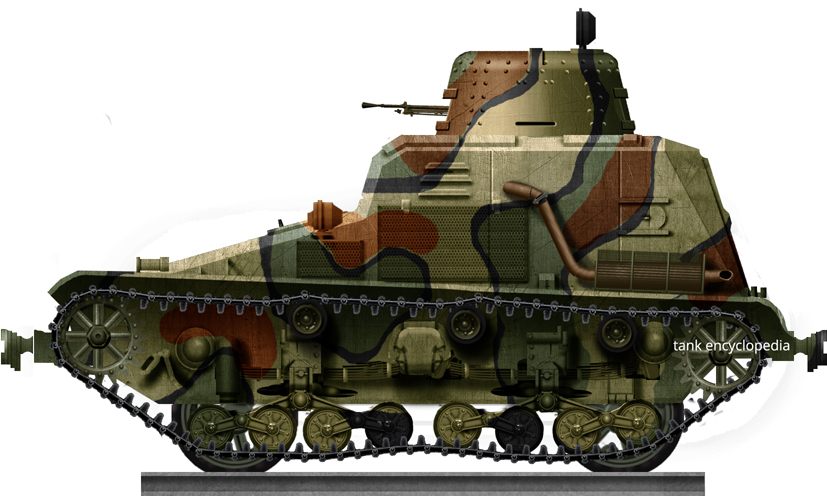

Type 95 So-Ki in regular Japanese livery.

Type 95 So-Ki in PLA service.

Several Type 95-So Ki tankettes linked up to tow a larger load. This photo clearly shows the wheels on the rails. The soldiers do not appear to be PLA, but could be NRA or of the Xishan army. Laiwu, Shandong Province, February, 1947. Credit: Mark Kauffman for TIME magazine.

Different view of the above. Credit: Mark Kauffman for TIME magazine.

Knocked out Type 95 So-Ki. Unknown date and location.

Type 95 So-Ki of the People’s Liberation Army, on display in the PLA Tank museum in Beijing. The museum’s layout has changed a number of times, hence why tanks appear to have moved from photo to photo.

Type 95 So-Ki, with passengers riding on top of the vehicle, Manchuria, 1940.

Type 95 So-Ki in Kubinka Tank Museum, Russia. Source.

Type 95 So-Ki in Kubinka Tank Museum, Russia. Source.

Type 95 So-Ki turret and upper hull. Source.

Type 95 So-Ki suspension detail. Source.

Sources and further reading

“Osprey Publishing, New Vanguard 140 – Armored Trains” by Steven J. Zaloga

“Osprey Publishing, New Vanguard 137 – Japanese Tanks 1939-1945” by Steven J. Zaloga

“World War II and Fighting Vehicles: The Complete Guide” by Leland Ness

“The Manchurian Myth: Nationalism, Resistance, and Collaboration in Modern China” by Rana Mitter

“Manchuria under Japanese Dominion” by Shin’ichi Yamamuro

“中國人民解放軍戰車部隊1945-1955” by Zhang Zhiwei.

www3.plala.or.jp, author – Akira Takizawa

On Aviarmor

“2004北京军博纪实:坦克装甲车篇(组图)“, an article on the Beijing Tank Museum.

Get the Poster of the ww2 Imperial Japanese Army Tanks and support us !

4 replies on “Type 95 So-Ki”

First I hear of wheeled tanks such as the Christie, but now this? Man… Where do these people dome up with such weird ideas?

Good article, as always!

There was a policy called “The Caged prison policy”(囚笼政策) used by Japanese occupational forced in China against Communist Guerilla warfare, and they’re a network of fortified bases connected by roads and railroads to block Guerillas from getting supplies or communicate with each other.

And the Communist Guerilla retaliate by ways including sabotaging railways and roads, harassing the Japanese soldiers in the forts and sabotage the Japanese supply lines. And these railway tankettes Can be used to patrol the railway and the normal road with same type of vehicle using minor part conversion.

interesting

That’s interesting and smart